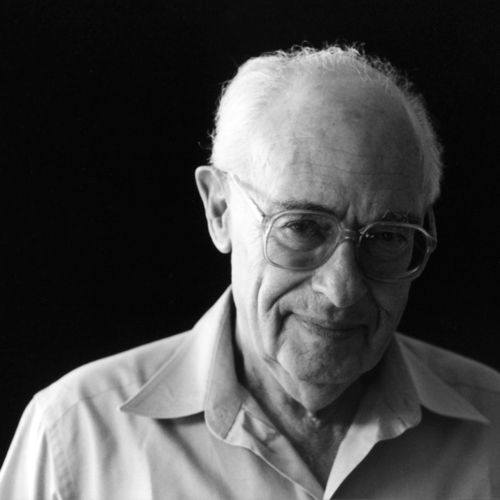

“Beware when the great God lets loose a thinker on this planet,” wrote Emerson. He might almost have been speaking of Georg Kuehlewind (1924-2005), the Hungarian chemist, linguist, philosopher and mystic who shocked heavenward all those fortunate enough to meet him.

There was always something a bit dangerous about Georg’s presence. It was not ill will: no one could be more compassionate. It was not a dark mood: no one could have a lighter wit, even in the face of horror. It was nothing unbalanced: no one could draw on healthier psychic roots. Yet there was a sense of things on the move, of discoveries that might take you who knows where, of having to put down your baggage and for once run free. Freedom: that was the danger in Georg’s presence, threatening to everything in us that wants stasis and self-protection. It included a great sense of liveliness, like pure oxygen, and this miraculous spaciousness occurred even in the simplest of conversations. As Georg’s beloved poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote,

See, I live. But from what?

Neither childhood nor future are diminished:

Existence, past all reckoning, springs forth in my heart.

Georg had a look, a glance, a way of communicating intensely with his eyes, that conveyed a special flavor of intelligent love. This glance was an expression of his total concern for everyone in the meditation groups he taught. When someone was missing from the group after a break, for instance, he always knew who it was, even in a group of 80 people he’d just met. Listening to the often cloudy meditation reports by participants, he would fasten on just the gem, the light, and refer to it later in the midst of his teaching. His own meditation reports opened the theme to us, always from a different angle, and with a different intensity, than we expected. Though the theme had seemed abstract and theoretical, his report could demonstrate a devotional, loving aspect we had not imagined.

When participants reported on their meditation with quotations or old thoughts, Georg would occasionally meet their contribution with a searching, “Do you know that?” For despite his scholarly approach to literature, music, linguistics, psychology and epistemology, Georg’s orientation toward spiritual worlds was experiential from start to finish. His own books are the account of what he himself experienced; they are not musings, or conglomerations of the insights of others. When asked about matters of karma or cosmic history of which he had no direct meditative experience, he was happy often to say he just didn’t know. Georg called himself an “empirical idealist”: that is, someone who lives in a world comprised entirely of meaning and makers of meaning.

In speaking of spiritual or personal matters, Georg was often moved to tears. He had lived through two Nazi death-camps as a youth, and suffered many losses and confusions of fate throughout his life. Perhaps, along with his spiritual work, these events had opened his heart. The impression he gave, however, was of being able to bear tremendous intensities of feeling before giving way to tears. And he could switch back, in a breath, from the overwhelm of feeling to a fresh, crystal-clear exploration of the subject at hand. He said, “We have tears, sometimes of sorrow, sometimes of joy, but then: back to the theme! That is always the gesture.” The whole spiritual path, for Georg, is there in our fundamental capacity to concentrate. To hear him teach was to be aware that this capacity can be deepened to a fantastic degree. It enabled him to listen more intimately to the world, so uncovering whole new ranges of experirence, as when he reported on a meditation that he was reluctant to put into words, that was not originally in words, but that he formulated like this: “To be addressed by someone gives existence. Every moment, Christ is in my heart whispering, ‘YOU ARE’.”

Despite his gifts to thousands all over the world, Georg did not claim to be a “good” man, and sometimes explicitly denied that he was one. Yet he said, “The only consequent life is the life of a saint.” He tended to the radical formulation, thinking each thought all the way to its end and beyond. When in his book on healings in the Gospels, he raises the question of whether human beings are born to die, he means it quite literally. In one of our last meetings, I asked him if he thought that really, through our spiritual work, we would one day, perhaps after many incarnations, be able to live in one body without laying it down to death. With complete seriousness, he said he did indeed think so. I asked for examples, and he came up with several, notably the legend of the Indian sage Bodhidharma, founder of Zen and a favorite of Georg’s. According to the story, after Bodhidharma’s death in China in about 540AD, one of his disciples met him walking back toward India, barefoot but carrying one sandal on a stick over his shoulder. The disciple rushed to Bodhidharma’s tomb, dug it up, and found it empty – except for the other sandal, which he’d left behind in his haste to emerge from the grave. Those of us who love Georg are probably willing now for him to progress through purely spiritual forms. Still, we would be delighted, if not entirely surprised, someday to find him walking in the Vienna woods, carrying one sandal, whistling silently, or clapping with one hand.

What if, as Georg suggests, the world were not meaningless, but vitally important? What if you had a mission, a mission urgent and vast enough to drive you into and through a whole human existence? It’s worth considering, since this is the message of the New Testament and especially of the “miraculous” healings explored in this deeply exciting book.

In Georg’s view, the healings are neither histories nor symbols. Rather, they are reports of events as meditations. This means that we can only approach them through a radically different kind of consciousness, an altogether new intensity of understanding. We miss everything if we read them as accounts of magic, or as supports to religious belief, or as literature.

The Prologue to the Gospel of Saint John, in words Georg said we almost “cannot take seriously enough,” claims that creation originally “was life in Him, and the life was the light of human beings.” Divine life, which creates the world, is also the light of human understanding in its original force. The same life, re-creating, became the substance of Jesus’ healings and can now become our understanding of them. This means that there cannot be a meditative reading of the healings that does not heal the reader.

Along the way Georg shows that expressions such as “glory,” “faith,” “life,” “power” and “word” are anything but the Sunday-school window-dressing, the spiritual garnish, they can seem to be to our cliché-worn eyes. Instead, as in his earlier Becoming Aware of the Logos, he explains them as terms of art, referring to specific spiritual processes that can make an immediate difference in the structure of our own minds. To work our way into their full benefit, such terms must become for us something like musical scores to a musician: in living them out, in performing them, we realize what they are all about.

Georg gives us an entire spiritual psychology in these pages. Its cogency, however, depends on our going through, with some energy, the “ponderings” and meditations he offers in each section of the text. To do this, it can be helpful to work with a friend or two. One enlivening way to approach a meditation is first to deny it, to argue against it, and then, releasing this intentional refusal, to find your way into a more intimate affirmation.

The healing direction of the texts takes us into a realm of non-duality, back from the sick individualism by which we cut ourselves off from the Source. Healing re-connects what the Fall split apart: the human and the divine. But our normal, body-oriented consciousness simply cannot take the intensity of non-dual experience of the divine. This is why the shepherds, for example, are afraid of the angelic host (Luke 2:9). To endure the light, to “bear the beams of love,” as Blake put it, we can awaken as I AM or the true self. Once we have learned this unusual strength of being, we also turn out to be strong enough to put aside the anxious sheath that separates us, and we can merge playfully with the very heart of the world.

All of this can seem too good to be true. We have forgotten that such things are possible. We have a hard time imagining them. We have long since stopped hoping for them. It can seem that to achieve the re-ordering of the universe that Georg describes is simply beyond us. And so it is! For the realm of healing is not to be achieved at all, but rather approached through moments of wonder and awe, the way innocent Parzival stumbled upon the Sacred Mountain. Nor does it exist for “us,” for the self-pointing, selfish self, but instead healing arises in our forgotten, silent, innermost and most unconsciously familiar self. If you are ready for the Great Adventure, Georg will lead you with a sure step through the brambles of terminology, up the foothills of insight, and suddenly out over an astonishing vista.

Michael Lipson